Blogs, Trending Videos

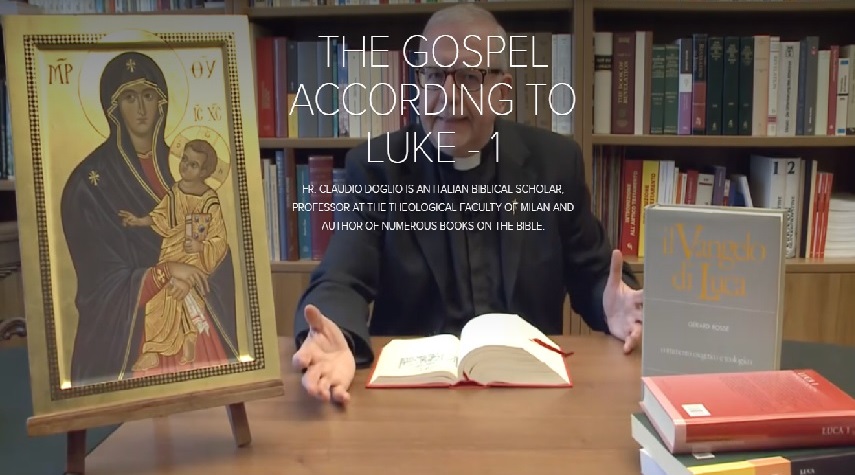

Bible for Catholic Nerds – 1.Who was Luke?

Who was Luke?

“Scriba mansuetudinis Christi”, this is how Dante Alighieri described the evangelist Luke: “Scribe of the meekness of Christ.” It is a concise and adequate formula. The evangelist Luke is, in fact, a skilled writer inserted in the culture of Hellenism and he has crafted a beautiful neat story picking up material from the tradition that preceded him; and he understood a fundamental aspect of Jesus: Meekness, says Dante Alighieri.

We could speak of God’s mercy. Luke is the evangelist of mercy. He narrates the human experience of Jesus as the culminating moment of the revelation of God’s mercy. But who is Luke?

At the beginning of these lectures dedicated to the third gospel, I will stop at the identikit of the author. The name does not appear in the narrative, but tradition presents him unanimously as Luke. We have some information about him from ancient ecclesiastical texts. His name appears in three passages of the Pauline correspondence in which it seems that this character was a collaborator of Paul, who defines him as “the dear doctor”; Luke had a good and affectionate relationship with the apostle and we found out that he was a doctor. Little else is added by the New Testament documents. From other ancient sources, we can retrieve some additional information.

He was originally from Antioch, the great capital of Syria, a cosmopolitan city; and he had probably become a Christian by encountering the first Christian preaching carried out by people who had been expelled from Jerusalem at the time of the persecution that exploded in the time of Stephen. Barnabas was also sent from Jerusalem to Antioch to organize the new community of non-Jewish Christians. Then Barnabas went in search of Paul, he took him to Antioch and together they formed a large number of people. It was precisely in Antioch that the term Christian was born to identify the new community. Among these new Christians in Antioch there was also a physician named Luke.

From the information we have from the ancient ecclesiastical tradition, we know that he died aged 84, long after Paul’s death. And so we can imagine that in the forties, when he became a Christian, meeting Barnabas and Paul, Luke was in his 40s. A middle-aged man with a beautiful profession; if he was a physician, he had a respectable social position. And considering the old standard, the fact that he could have studied as a physician tells us that he belonged to a wealthy family, with good financial resources, which is why Luke had studied medicine as a young man and of course he had a good classical Greek literary culture.

Greek was spoken in Antioch; it was one of the capitals of the Hellenistic world. Probably, among his many studies this physician, could also have seen the translation of the bible into Greek, the bible that we call ‘of the Seventy.’ It is possible that this man also read some passages from the Hebrew Scriptures; maybe he was a man in search, interested in various cultures, taking into account that Antioch was a city in which people converged from all the old eastern surroundings. He was used to meeting people of different cultures, languages, of different religions, and among these people he also met some disciples of Jesus of Nazareth; and it was the decisive encounter of his life.

An encounter that marked the physician Luke for the rest of his days. He was fascinated, admired by the character of Jesus; wanted to meet him, got baptized, became a Christian. He befriended Paul, strongly bonded with him and accompanied him many times. He wrote not only the gospel but also The Acts of the Apostles and it is precisely in The Acts of the Apostles where we can obtain some important information about the presence of Luke following Paul.

In fact, in Acts, there are some passages written in the first person plural. It is a way in which the writer lets it be understood, with fine modesty, “I was there too,” without saying it. For example, in chapter 16, arriving in Troas, Paul and his collaborators stopped there for a few days; then the narration continues changing person: “We left Troas, we sailed towards Samothrace; we got to Neapolis, then we got to Philippi.” The first person plural reveals that the writer was there and, therefore, accompanied Paul on a sea voyage from Troad to Philippi. When Paul leaves Philippi, the story resumes in the third person plural.

We reconstruct that Luke, on that occasion, stopped at Philippi. Most likely it was his adopted city; native of Antioch, he arrived together with Paul to the great city of Philippi, a Greco-Roman city in Macedonia, northern Greece, and remained there. He remained at the head of the Christian community that had been formed in this new urban reality; and he remained as a formator, animator of the community, until years later Paul, returning from a trip stopped in Philippi, and from that moment Luke joined Paul and accompanied him during the last trips without leaving him.

Probably, as a medical expert, he had noticed that the apostle had serious health problems and was therefore close to him as an assistant, as a physician friend, capable of curing him. Together they went to Jerusalem where they arrived for Pentecost of the year 58. On that occasion Paul was arrested and imprisoned for two years, awaiting trial. In those two years, Luke was lucky to stay in and around Jerusalem. It was a journey through the Holy Land that lasted a long time and offered him an exceptional opportunity: to know the places, but above all to know the people; meet eyewitnesses, the relatives of Jesus, those apostles who were still present in Jerusalem. Meeting many other people who had seen Jesus some thirty years before.

There seem like many years, but for a middle-aged person, they are few and one has an excellent memory of things that happened 30 years ago. If, on the other hand, these are important and significant facts that have affected the person and the imagination, then the memory remains very fresh. Luke in those two years had the opportunity to travel from Jerusalem to Caesarea, meeting many people, collecting documents and finding written material, participating in liturgies of the Christian Jewish community.

He did not know Hebrew or Aramaic, but the Jewish Christians in Jerusalem knew Greek because it was the lingua franca that everyone used, and therefore Luke had the opportunity to visit the places where the ministry of Jesus took place. He went to Jerusalem, he went to Bethlehem, probably visited Nazareth; got an idea of reality and learned many things from eyewitnesses. He stayed those two years to be close to Paul while he was being held in prison in Caesarea Marittima. When the governor changed, it seemed that the process would be resolved favorably, but Paul appealed to Caesar and then the prisoner was sent to Rome by sea, naturally. Luke embarked with Paul and went to the capital of the empire. They were shipwrecked near Malta, they were saved, they spent the winter there and the following spring they continued their journey arriving in Rome.

Paul remained awaiting trial for another two years, in house arrest, and his assistant Luke, was lucky, this time, to be in Rome with Paul. While Paul was in prison and had to remain under house arrest, in military custody, under a soldier on guard; Luke was free and could move; and get to know the community of Rome. At that time, in the early sixties, there was Peter in Rome, there was Barnabas, Silas had arrived there, also Timothy as well as Paul. And Luke meets Mark, who in those years was collecting materials for his gospel. At the beginning of the sixties inside the Roman community, Mark has the task of putting together documents that were already circulating about the preaching of Jesus; and Luke adds this new knowledge to his experience.

After two years awaiting trial, it all ended in a soap bubble. The accusers did not appear; Paul was released because the fact had no evidence; and Luke resumed his travels with Paul for a few more years, from 63 to 67 when they returned to Rome. And on that occasion the apostle was arrested again and this time sentenced to death. Under Nero, Paul was beheaded on the Via Ostiense and buried there.

Then Luke, not having to follow the apostle Paul, he retired to private life, but he did not shut himself up in his private world; retired to a city in Greece, not well identified, where he certainly became the guide of a Christian community. There he spent the last years of his life. When the apostle Paul died, Luke was about 60 years old, he was his contemporary, perhaps a little older, only he lived another twenty years. And then throughout the ’70s and’ 80s, he had a chance of collecting ideas, memories and literary material that during all that very important apostolic experience from countless trips with Paul he had gathered.

How does Luke compose his gospel? He tells it at the beginning of the text. It is the only case in which an evangelist introduces a method prologue. It is typical of Hellenistic writers. Luke actually has a Hellenistic writing culture and begins his book with a complex phrase that occupies the first four verses in which he summarizes the different stages of his work. Let’s read this text because it helps us to frame his literary method well:

“Since many have undertaken to compile a narrative of the events that have been fulfilled among us, just as those who were eyewitnesses from the beginning and ministers of the word have handed them down to us, I too have decided, after investigating everything accurately anew, to write it down in an orderly sequence for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may realize the certainty of the teachings you have received.”

With these words, the Evangelist Luke presents us with the series of stages that from the historical event of Jesus led to the writing of his book. The first volume of his work, in two volumes (because the second part is The Acts of the Apostles). First of all, there are the ‘events that have occurred among us that concern Jesus of Nazareth.’

Not ideas, not myths, but concrete historical facts, dated and placed in time. An important fact that had eyewitnesses. Luke uses the same term which Greek historians like, and speaks of ‘autoptai’ (αὐτόπται) = ‘those who see with their own eyes.’ We use the term ‘autopsy,’ which seems to have to do only with corpses, but it is a technical term to indicate ‘verification in person’ of a fact, there are eyewitnesses who from the beginning became ministers of the word, servants of the ‘Logos.’

These are the apostles, they knew Jesus, they lived with him, they knew him well, they became servants of their preaching, they have told others what they have seen and heard. The preaching of the apostles, therefore, it is the first important step, after the historical event of the word. Jesus reveals himself as the Messiah, Son of God. Eyewitnesses find it, experience it and they talk to others about what they have seen and heard. Their experience is not only transmitted verbally, rather it requires a written form. Luke says that many have tried to tell the facts in order. I do not think it refers only to Mark who had already written, and to Matthew that maybe he hadn’t even written yet and was in a different environment from where Luke lived.

The evangelist refers to many, therefore it means that in the first years, in the first decades after the Passover of Christ, many short texts had to circulate that collected some information, texts of the words spoken by Jesus, accounts of events related to his life, especially the culminating episodes of his passion, death and resurrection.

During his travels Luke met many eyewitnesses and probably collected many of these documents; so he decided to make a literary work himself with precise research. Also in this case, he adopts a technical term from the Greek language (ἀκριβῶς = akribos) which has also entered our English vocabulary, although it is used only in a literary context. (ἀκριβῶς = acribía: “exact, sure, scrupulous.” Refers to rigorous accuracy, to exactitude or to precision in the cultural sphere).

Luke as an accurate and documented historian says that he has collected oral testimonies and written documentation and that he personally reworked them. It is an important wording made by Luke, that is, he has written, cut and amalgamated, corrected, adjusted all the material he received, to compose a literary text that fit his intentions.

This work is dedicated to the illustrious Theophilus, a character about whom we know nothing. The adjective ‘illustrious’ = κράτιστε = krátiste, in Greek, was used by high officials of the Greco-Roman administration, so this would suggest a real character, present in the city where Luke lived, to whom the work was actually dedicated, probably the sponsor or an authorized person who could support the publication of the work and make it available to the public. Some have also wanted to see simply a symbolic name; ‘Theophilus’ (Θεόφιλε) means ‘friend of God.’ And beyond the concrete historical fact of the dedication, this book is addressed to you, if you are a friend of God, if you are interested in knowing the story of Christ; then, this work was written for you; and it was written so that you can realize about the solidity of the teaching you have received.

This Theophilus is not a beginner, he has already been catechized, he is already a Christian, he has received a teaching. Luke’s work serves to demonstrate that the Christian message is founded, the doctrine preached by the apostles of Jesus it is not far-fetched, it has historical and literary strength. Luke, in turn, became a minister of the word and he offered us a splendid text: the third gospel that we want to read as a reliable documentation of this important event.

God’s mercy has been made known and thus, we can appreciate how good this scribe of the meekness of Christ was.