Blogs

History of the Composition of the Fourth Gospel

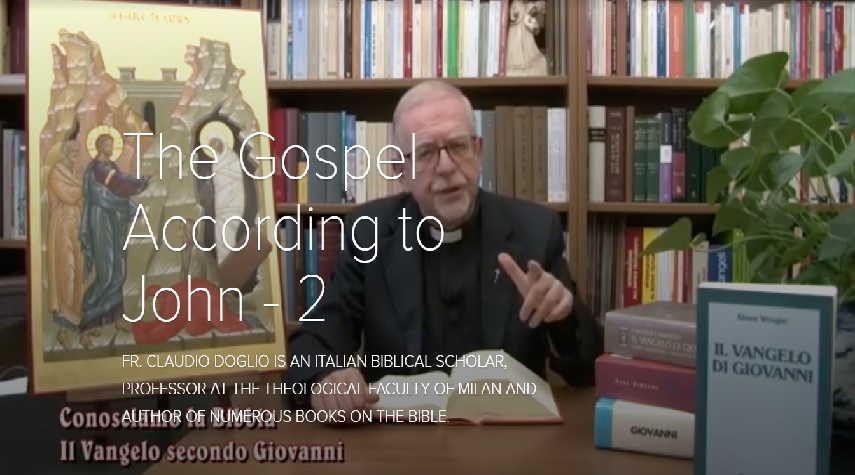

Who really is John, the theologian, the author of the fourth gospel, symbolic writer who composed a wonderful spiritual gospel? The text does not name or describe him, but the ancient authors, without a shadow of a doubt, always identified him with the disciple John, son of Zebedee, brother of James, one of the twelve apostles.

Some modern scholars have doubted this identification because the author of the fourth Gospel is a profound man who reveals great theological and literary knowledge, while the apostle John is a young fisherman from the Lake of Galilee, according to the Gospel account. Therefore, an attempt was made to find other hypothetical authors, especially linked to Jerusalem and to the priestly environment.

However, a recent hypothesis, in my opinion, has overcome this difficulty and has put together the various possibilities, that is, believing that the author of the fourth Gospel really is John, one of the twelve apostles, son of Zebedee and a priest of the temple in Jerusalem, therefore, linked to the cultured environment of the holy city, to the priestly family and, therefore, the bearer of a culture, of remarkable literary experience.

Why, then, do we find him a fisherman on the shores of the lake of Galilee? Because the priests of the temple in Jerusalem were not busy all year long in the sacred offices of the temple. They usually had a job and probably John was not simply a poor fisherman, but he was the owner or rather the son of the owner of a fishing company.

Based on studies and discoveries, it is possible to believe that a priestly family in Jerusalem could engage in commercial craft activities, as it could be a fishing business. John, at the time of the historical events of Jesus, was very young. We do not have information to say how old he was, but he could have been 12 to 15 years old, therefore, very young.

He did not write the gospel during the life of Jesus, but the finished work, that we now have in the editions of our bibles, that we read as the fourth gospel, was born at the end of the 1st century. Doing the math quickly, If the year of Jesus’ death and resurrection is the year 30, and the gospel ends around the year 100, from the historical events to the end of the writing of the text, 70 years passed.

It does not mean that John wrote it 70 years later. I said the composition period is over because this work took a long time; 70 years is a lifetime. If we imagine that John was 15 years old, add another 15 years and he would be an 85-year-old man. It is not an extraordinary age because it is documented in other characters, that someone could be a few years older or younger.

However, this means that the fifteen-year-old spent the other 70 years of his life meditating on that exceptional experience he had as a young man. Three years of his youth were marked by the presence of that extraordinary man. With the intelligence and memory of a young man, John memorized much of what Jesus did and said, from experience and memory, but he did not put it in writing immediately. It is not a cast text; it is a thoughtful text.

Before writing it, John thought for a long time, he did a symbolic operation, he put together all the details of his memory. He remembered many details of the life of Jesus, of his character, of his words, of his actions, of his relationships with the disciples, with the authorities of Jerusalem. He meditated personally and communicated his meditations orally to others. While telling, he intuits the meaning of a particular text and deepens it. He goes back to telling it, and he himself understands it more, and then corrects the way of telling it, to help the listener understand the deep spiritual meaning of what it means.

This operation lasts 70 years and the most likely thing is that the writing of the text has not occurred in one fell swoop, with a single publication that arrives after 70 years, but must have gone through several editions.

It’s a working hypothesis, an interesting hypothesis that came back into fashion by an American scholar Urban von Wahlde, who published a great commentary on the fourth gospel in 2011, of which this 700-page volume is the introduction, just the introduction, with a detailed reconstruction of three hypothetical editions of John.

The merit of this hypothesis, which he calls ‘genetics’ is to value the same text, and points out how in the Gospel of John there are tensions of vocabulary, changes and reconstruction of the composition of three different works.

I try to explain myself better. It is possible to imagine that the disciple John, in the early years, not only meditated, but also preached the signs that Jesus performed and began to produce a written account. It is what, traditionally, for over a century, has been called the ‘gospel of signs,’, that is to say, a part of John’s story where 7 signs performed by Jesus are presented. Seven miraculous deeds performed by which Jesus wants to signify his own messianic work with which Jesus reveals the face of God.

It is a first possible archaic edition perhaps also written in the Semitic language, probably in Hebrew, in Jerusalem in the early years. We can imagine throughout the ‘40s to ‘50s; that is, in a very close environment from the geographical and historical point of view to the events narrated. This first Joanine text becomes the basis for further meditation.

Meanwhile, persecution broke out. The disciples of Jesus depart from Jerusalem. They come to Samaria, they come to Antioch in Syria. The horizon widens and knowledge deepens and in this second phase, around the ‘70s, in which Jerusalem is besieged by the Romans and Christians have to leave, like many Jews, a second edition is born; in the meantime, he has made enormous strides forward from the point of view of theological understanding.

These years have not passed in vain. As he matured, John himself understood better and he rewrote his Gospel doubling the volume. He rewrites part of the text he had already written and expands it. For example, the story of miracles, which he always calls signs, is accompanied by discussions. After having performed a sign, Jesus collides with the Jews; and here we find problematic terminology in John.

He often calls the Jews adversaries of Jesus and it is precisely from this use that the almost derogatory tone was born which in our languages has the term ‘Jew.’ John calls ‘Jews’ not all those who belong to the Jewish people, but only the group of authorities who stubbornly oppose Jesus. In the texts of the first edition, instead, he spoke of high priests, Pharisees, scribes. The same terminology used by the Synoptics. When the text goes deep, the term ‘Jews’ appears to characterize a part of those opponents that deny validity to the preaching of Jesus. They don’t believe in him, not accept him and refuse him. This step is caused by the historical fact of the opposition of the Christian community, already mature, with synagogue authority that only a group of intransigent Pharisees assumed, to survive the disaster of the destruction of Jerusalem.

And in this controversial climate, which is also noted, for example, in the substrate of the Gospel according to Matthew, John conducts an in-depth analysis and responds to Jewish controversies by presenting a deeper teaching from Jesus and raises the level of Christology. This second edition, certainly in Greek to be understood by a larger audience, presents Jesus with divine nuances.

By now the awareness that this man is God has matured and presents it with divine characteristics. This second edition, which has markedly marked a maturation in the text, also created problems because it gave inspiration to those who wanted to combine the Christian message with the Greek culture, especially the Gnostics, and a Christian Gnostic thought appeared that misinterprets John’s position and believes that Jesus is God, only God, and man only in appearance.

It doesn’t seem possible to us, but it was actually easier for an ancient thinker to imagine that Jesus was a god who resembled a man, rather than truly considering him a man. Having performed prodigious signs, easily the ancient man, including the intellectuals as well, would have said that he is ‘god in human form.’ But that human form was only appearance. Think of the Odyssey; how many times Ulysses meets with Athena without realizing that it is her because the goddess had taken the form of this or that character and gave him the right advice at the right time; she gives him good advice and then disappears. Since ancient times the Greeks are used to the appearances of the divine and Jesus could easily be one of the many appearances of the divine.

This is what the Gnostic world thinks and seems to continue to affirm that Jesus is a god who looked like a man. This position is dangerous. Meanwhile, John moves to Ephesus, great capital of the Greek world, a Hellenistic city where Gnosticism was very strong. It is precisely in the Johannine community of Ephesus where a schism, an internal division occurs. John has to write the first letter.

He must write a text in which he reaffirms that Jesus is truly man. He is God, but really made flesh, human. He begins the first letter by saying: “What was from the beginning, what we have heard, what we have seen what our hands have touched, to the Logos of life; because life was manifested, and we have seen it, and we testify, we announce that to you.” The antichrist is the one who denies that Jesus became man. It is an ‘antichristic’ position, of opposition to Christ, to deny the flesh, and thus the third edition was born.

John, now old, 70 years away from the historical events, takes up his book for the third time and integrates it; for example, he adds the prologue, in which are the mature and solemn affirmations of Johannine theology. The Logos became flesh and dwelt among us and now we see his glory. Now he came to a deep understanding.

The third edition corrects the possible Gnostic derivations, it slows down Christology and keeps it on the right path: Jesus is true God, but also true man. And it is possible that in addition to this third edition there has been one more retouch due to the community itself because John has built a community of people, in turn he has disciples who listen to him, follow him and has collaborators who write, expand. They are people who think, reason, they are pastoral collaborators and they are what we imagine as priests, deacons. They are people who in turn preach, teach and collaborate with the elder witness, the disciple loved by Jesus.

It seems that only in this third edition appears the writing of the disciple whom Jesus loved because now we are at the end, when John becomes the ideal model and the criterion of interpretation of Jesus. To follow the testimony of the disciple whom Jesus loved is an indispensable condition to remain in the truth, otherwise, one runs the risk of inventing a Jesus at personal taste. The concrete risk existed in the Johannine community of Ephesus, towards the end of the first century, and this last edition, which is the canonical one that we now read, contains the previous layers.

It is a wonderful work that has grown over time, very well organized with an intelligent criterion, from a prologue to an epilogue, and two large parts, the gospel of the signs and the gospel of the hour, almost like two buttoned books in the center with chapter 12. First, Jesus performs 7 signs to signify God’s action, then, when his time has come, he entrusts the custody of the word to the disciples and carries out the event of his glory.

The cross is the moment of the greatest revelation. And the witness, John, present at the foot of the cross, when he sees the water coming out of the side of Christ along with the blood, recognizes the gift of the Spirit, that Spirit that makes humanity capable of meeting God, that makes John able to write a spiritual gospel; and the eyewitness testifies and write these things meditating on them for 70 years, so that you too may believe.v