Blogs

The Path of the Word of God

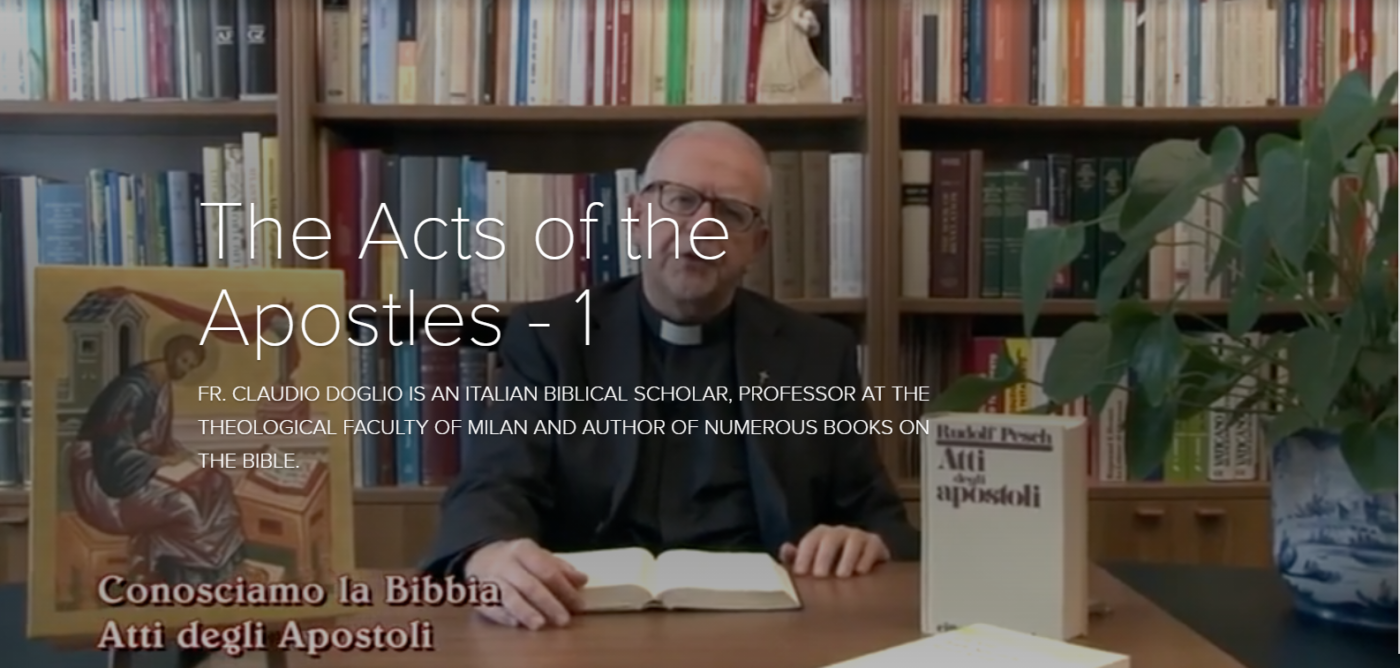

The Acts of the Apostles – 1

.”In my former book, Theophilus, I wrote about all that Jesus began to do and to teach until the day he was taken up to heaven, after giving instructions through the Holy Spirit to the apostles he had chosen.”

Thus begins the book of the Acts of the Apostles, which tradition attributes to Luke, the third evangelist. The beginning makes an explicit reference to a previous work. In Greek, it is called ‘logos.’ It is the first ‘logos’ that the author composed. ‘Logos’ in the sense of a speech. It is a narrative speech in which he presented the human history of Jesus from the annunciation to the death and resurrection and the apostles’ universal mission.

The other evangelists stop there. Instead, Luke decided to write a second ‘logos,’ another long narrative speech to continue their formative work. Like the third gospel, also the Acts of the Apostles are dedicated to Theophilus. It may be that it is an actual historical figure who lived in the environment of Luke to which the author dedicates this text. Perhaps he was an authority on the Greco-Roman system of administration. At the beginning of the third gospel, he is described with the adjective ‘κράτιστε’ = ‘kratiste,’ which is a title of honor that somehow corresponds to our ‘your excellence’ and it is given to a person of social importance. This person must have approached evangelical preaching in adulthood and in recent times. Luke decides to write his two volumes of a unique work for this specific character to help him realize the solidity of the teaching transmitted in the preaching in the catechetical formation.

Theophilus, however, is also a symbolic name; in Greek, it means ‘friend of God,’ and then the ideal recipient is every person who in some way considers themself a friend of God. Suppose philosophy was highly esteemed in Greece, and the sage is a ‘friend of knowledge,’ now in the biblical language of Luke, the ideal is the ‘friend of God,’ who seeks wisdom that comes from above and does not conform to the ideal is the ‘friend of God,’ the one who seeks wisdom that comes from above and does not conform with earthly reasoning.

The theological proposal that Luke makes is historically based; it is not a collection of made-up fables. The doctrines that the Christian community is presenting to the world are not human inventions; they are the revelation of God through the person of Jesus, recognized as the Son of God; and then through the testimony of the disciples of Jesus who, leaving Jerusalem, have gone to proclaim the gospel to the ends of the earth.

The intention of the second work of Luke that we want to read and comment on in these videos is precisely to show the path of the Word of God, from Jesus to all humanity through the work of the first disciples. Departing from Jerusalem, preaching spreads like gunpowder; it spreads through Judea, Samaria, reaches the city of Antioch in Syria, spreads to Europe, and reaches Rome.

The book will end with chapter 28, with the arrival of Paul imprisoned in the empire’s capital. Luke does not pretend to tell the history of the Church, that is, all the events of those years; does not even write a biography of Peter and Paul because the first part is incomplete, where above all Peter emerges; and the second part where Paul is the absolute protagonist. For example, it is incomplete because it does not end; it looks like unfinished work. Paul arrives in Rome awaiting trial; the narrator says he waits for two years and stops there.

He knows that the process acquitted Paul, who is starting over his work, now free. Paul continues, but this the book of Acts does not say anything about it; so we must be clear about the following: it is not the history of the whole Church or the works of all the apostles, even less the biography of Peter and Paul, but acts, actions, gestures of the apostles, especially of Peter and Paul, but also others like Stephen, Philip, and Barnabas.

Luke, following his Hellenistic culture, has collected a large amount of historical material and has reworked it with dramatic skill in presenting scenes; it is a story of evangelical preaching in pictures; what Luke does is a theological discourse, but historically founded; he is a historian who reconstructs the passages; rebuilds them competently, with data, with precise geographic locations, with highly detailed local cultural notes, but he is not interested in an encyclopedia of facts; he is interested in a theological message that conveys through pictures, told with art, and giving great weight to the speeches.

It was a classic system in Greek historiography to introduce the discourses of protagonists through which the author can present the thoughts of the various characters and deepen a reflection on the meaning of the events narrated. In the Acts of the Apostles, we will find many discourses, first by Peter and then by Paul, speeches that somehow summarize the evangelizing action of the apostolic community.

They are certainly not verbatim transcripts. Luke imagines what this character could have said in that particular situation. Let’s now follow the proposed text in order, and we will read it, framing the narration and giving the necessary indications for a fruitful reading.

These moments of conversation that I have with you have an introductory purpose. Ideally, you, the listener, in turn, become a reader and look in your bible, in the biblical library, the book of the Acts of the Apostles. After the four Gospels, in the New Testament, we find this text. It would be nice if you have it at hand and read it, connecting with this treasure, this wise experience that the evangelist Luke wanted to transmit to Theophilus, that is, to each one of us, so that we can realize the strength of what we have been taught.

Therefore, the first chapter is a kind of closure of the gospel, a sort of buttoning: taking a step back to take a step forward. For each buttoning, the fabrics must overlap. Somehow, Luke takes up the story of the appearances of the risen Christ to complete the narrative with what the apostles did after the ascension of Jesus to heaven.

So, he starts by briefly counting the encounters of the risen Christ with the apostles. Luke points out that they often met during meals; it is an essential detail. The group of apostles experienced the risen Lord at the table. While they were gathered to eat, the Risen One joined them, and he would give them a kind, fraternal speech at dinner. This is at the origin of the celebration of the Eucharist; Christian communities have taken the custom of dining with the Lord to celebrate the ‘Kyrios’ – the Lord’s Supper, repeating what Jesus did at the Last Supper before his death, and that Jesus resumed after the resurrection from the dead with his disciples.

After they no longer saw him physically, the apostles continued to eat with the Lord, remembering what the Lord said, what the Lord did. Thus the Eucharist was born, composed by the liturgy of the Word, with the reading of texts and eucharistic liturgy where consecrated bread is consumed.

On those occasions of coexistence, the risen Christ gives some critical indications to the disciples. He invites them to stay in Jerusalem, awaiting the promise. It’s the relaunch of the promise of the Holy Spirit as a gift from God. It is a critical theological discourse; the Son’s work culminates in the work of the Holy Spirit. The Son gives the Spirit; the Son, risen and ascended to heaven, becomes the mediator of an outpouring of the Holy Spirit that will give life and sustain the Church’s action.

In this context of coexistence, the disciples ask Jesus: “Lord, are you at this time going to restore the kingdom to Israel?” The apostles have not yet fully understood what the mission of Jesus is. They imagine the risen Christ finally organizing an earthly kingdom. Christ is the official title of the Davidic king, and therefore if Jesus is the Messiah, he is the rightful king, the heir to the throne; and the heir to the throne must organize the kingdom.

The disciples wait for this new earthly organization at any time. The answer that Jesus himself gives and that Luke puts at the beginning of his book is programmatic: “It is not for you to know the times or seasons that the Father has established by his own authority.” Times and seasons are a technical expression; it refers to ‘kairos’ and ‘kronos’: the two ways of indicating time: the general measure of all the passing of the years, of the days, of the months, and the appropriate suitable occasion to do something, “it is not for you to know….”

Jesus eliminates any perspective on reasoning and timing, and Luke highlights it well. Probably in his day, when he composed this text, many years later, some 50 years after Jesus’ Passover, there was a heated discussion about the times and moments of the glorious coming of Christ. It is not the Church’s job to reason about when it will come. Jesus promises. ‘You will have the strength of the Holy Spirit that will descend upon you, and the Spirit will make you capable to be my witnesses in Jerusalem, throughout Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth.”

This geographical expression gives the narrative scheme of Acts. The first part will be set in Jerusalem; the second part will mark the departure of the holy city with the opening to the region of Judea and Samaria to later give space, in the third part of the story, to the great mission of Paul that crossing many regions will reach Rome, understood as the ends of the earth.

With brevity and great sobriety, he narrates the ascension of Jesus to heaven; He goes carried by a cloud and disappears in view of the disciples who remain with their eyes looking up; and as on Easter morning, two men in white robes had given the announcement of the resurrection to the women who had come to visit the tomb, thus on this day of ascension, 40 days after Easter, two men in white robes shake the apostles, saying: “Men of Galilee, why are you standing there looking at the sky? This Jesus who has been taken up from you into heaven will return in the same way as you have seen him going into heaven.” Again, we note a correction point against these speculations on the future coming of Christ: “Why are you standing there looking at the sky?” It’s like saying: ‘Do not stay with your arms crossed,’ do not get lost in these abstract musings. There will come one day… it is not up to you to know when it will be… you be busy on what you have been entrusted.’

They returned to Jerusalem because Jesus had taken them out to the Mount of Olives, a mountain in front of the city of Jerusalem, beyond the Kidron Valley. They return to the city and stay in that house where they had found hospitality for the last supper and the following days. It is what we usually call ‘the cenacle.’ In that house that probably belonged to the family of the Evangelist Mark, the Christian community is housed. That private house becomes the Church’s home, and in this domestic family context, the community meets.

They remain steady in prayer, together. All 11 are listed, along with Mary, the mother of Jesus, and his relatives. It is a community of around 120 people. The group is not only 12 but includes a hundred people. They are the Galileans linked to Jesus and some inhabitants of Jerusalem who recognized him as the Messiah.

In these days that precede the coming of the Spirit, it is a question of rethinking the role of the twelve, and Peter takes the floor with the first speech that Luke puts on his lips. It is a speech in which the mourning for the loss of Judas is reworked; it is a recent wound: ‘One of us, one of ours, was responsible for the death of Jesus; it had a bad ending and walked away. Jesus had constituted us as 12, to be the new patriarchs of the new Israel and therefore, that number 12 must be reinstated.’

Peter guides the community to rethink the tragedy they have lived in; there has been a traitor, a tear, something to rebuild, and it is necessary to resume the discourse and choose a new apostle. They propose some criteria: it must be someone who has lived with Jesus throughout his public ministry, from baptism to death, and must have witnessed his resurrection. Only two people correspond to these criteria. They could have integrated the two … the two could continue bearing witness, but only one should enter the number twelve, precisely to constitute that particularly significant number.

The two are Joseph called ‘Barsabbas,’ nicknamed Justus and Matthias. They choose them based on the criteria proposed by the apostles, but then the alternative between Joseph and Matthias is left to chance. The apostle’s lots are cast, and Matthias’s name comes out. It is interesting to note how the apostles before the gift of the Spirit do not feel capable of choosing and deciding, and somehow the choice of the twelfth apostle is left to divine intervention through luck. And Judas joins those who hated Jesus and lost their place, but Matthias will come in his place united with the school of 12.

In this moment of rethinking history and waiting for the mighty event promised by Jesus, finish the first chapter preparing the remarkable story of the first Christian Pentecost, which is the event that marks the opening of the doors and the departure from the Church, the beginning of the great work of apostolic witness.