Blogs

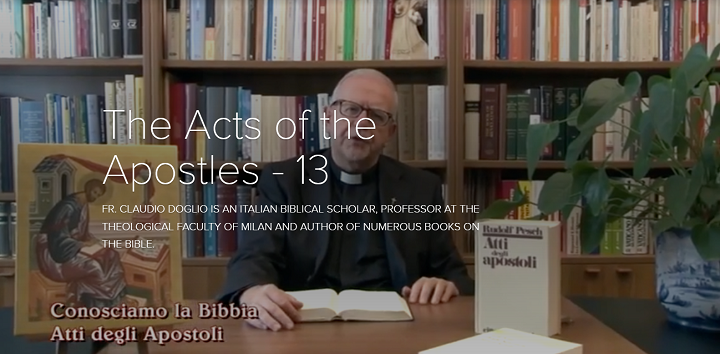

13. Paul’s Second Journey

Acts of the Apostles

After the Council of Jerusalem, Paul and Barnabas prepare for a new mission. In Jerusalem, the apostles and priests met to discuss a critical issue raised by Paul and Barnabas. Having announced the Gospel of Christ to many non-Jews, the question arose whether, before being a Christian, one should be a Jew and therefore ask the new converts for the complete observance of the Law of Moses.

The apostles in Jerusalem evaluated the situation well and solemnly decided that believing in Jesus Christ was enough to be saved. Therefore, it is enough to adhere with faith to Jesus, recognizing him as Messiah, Son of God, Lord. Reinforced by this apostolic approval, Paul undertakes a new mission, but with Barnabas, there is a minor disagreement. Let’s remember that during the first trip, they were accompanied by John called Mark, the evangelist, a relative of Barnabas, but this young man from Jerusalem, when he arrived at Athaliah, was frightened and did not continue the journey through the mountains of Taurus; he decided to return to Jerusalem. When now Barnabas wants to take Mark with him, Paul opposes, believing that he is not suitable for the mission since he left once. The two discuss and decide to separate. Paul leaves with Silas, while Barnabas and Mark go to Cyprus.

Paul wants to return to the heart of Anatolia – this is the name of what today is called Turkey. There, Luke, the narrator of the Acts, has presented the birth of some Christian communities in Antioch of Pisidia, Iconium, Lystra, Derbe. Paul wants to visit these communities where he had announced the Gospel a few years earlier and wanted to continue the work of formation. He passes through Tarsus, his hometown; the exit is always from Antioch because it is Paul’s mother church. Through the Cilician way, a narrow gorge, and today a scenic tourist place par excellence, Paul and Silas arrive at the Anatolian plateau, and Timothy joins the group.

Timothy is a young man, son of a woman who became a Christian during Paul’s first mission; perhaps when his mother became a Christian, Timothy was just a child; now he is a young man; he has grown in the Christian faith, and Paul takes him, and Timothy will become his ideal disciple. They continue the itinerary through the central region of Anatolia, sometimes changing the direction of their journey due to unforeseen events.

It is interesting how the narrator gives theological motivations at the beginning of chapter 16 of the Acts, where these direction changes are narrated. On one occasion he says, “The Holy Spirit did not allow it.” In another case he says, “The Spirit of Jesus prevented it,” as if to say that in case of some unforeseen event that has determined a change of itinerary, they have read it as a divine intervention to guide the path of the apostles to Troas, a Hellenistic city near the ancient site of Troy, the city sung by Homer. In this city, Paul, Silas and Timothy also find Luke, the author of the book.

We remember him because precisely at this point, in verse 11, it changes from the third person to the first person. The narrative moves from the third person to the first-person plural. Paul had a dream; he dreams that they sail from Troas, making a straight run for Samothrace, and on the next day to Neapolis. In the morning, he comments with his collaborators that night’s dream, and they understand that it is an invitation to cross the sea and reach Macedonia, the north of Greece. It is Europe. This passage is fundamental; the Gospel comes to Europe, and at this point, the narrator says: “As soon as he had that vision, we tried to go to Macedonia, convinced that God was calling us to announce the Good News.”

This ‘we’ suggests that the writer is included. At this point, a section begins that scholars have called the section ‘we.’ In the book of Acts, there are several of these inserts, and putting them together, we would have a kind of travelogue. Probably Luke, a collaborator of Paul, his beloved companion, has kept a logbook, noting the stages in the navigation and when, several years later, in the tranquility of old age, he checks all these notes, used that logbook, and can give us detailed and precise indications about the duration of the trip, about the stops.

It is a typical old ship of small coasting, where the displacements are from port to port. Sailing is by day, and in the afternoon, the boat must moor in a safe harbor and resume sailing the following day. So, leaving Troy, they sail to Samothrace, an island in the north of the Aegean Sea, and the next day they resume navigation. They disembark in Neapolis, the port of the city of the Philippians, which is located immediately inland on a large plain. Arriving in Philippi, the four preachers find a large Roman Hellenistic town, mainly inhabited by foreigners, with minimal Jews. There are no synagogues in Philippi. Paul always used to begin his preaching from the synagogue because he had the opportunity to announce to the Jews the coming of Christ. Where there was no synagogue, the Jews had the custom of gathering for the Sabbath prayer near the water or a river or the seashore or spring, a fountain.

Then, Paul and his colleagues, knowing where the meeting place is on Saturdays, come and find only women. The old rules for prayer in the synagogue on Saturdays required at least ten adult men, and if that minimum number was not reached, the official Sabbath prayer could not be done. There were only women, and therefore, it could not be done. Four men have arrived, but there are only four. Paul does not let the occasion pass because there are only women, but he is equally dedicated to preaching and proclaiming the Gospel with that female audience. And among these people there is a lady named Lydia; she comes from the interior, from the land of Ephesus, from the city of Thyatira; she is a purple merchant, probably a textile industrialist, entrepreneur, who has opened a business also in the rich and lively city of Philippi.

This woman listens to Paul’s speech and, as the narrator says, “the Lord opened her heart to pay attention to what Paul was saying.” She accepts this preaching and offers to lodge the four evangelizers. Luke, with a fine irony, comments: “She offered us an invitation, ‘If you consider me a believer in the Lord, come and stay at my home,’ and she prevailed on us.” They were probably delighted with that hospitality because they had no accommodation; they had perhaps slept under the bridges. Therefore, being guests in this lady’s mansion was a considerable advantage.

Lydia’s house becomes a ‘domus ecclesiae,’ becoming the home of the Church. It is in this environment that believers gather; she asks for baptism, together with the family. The husband and children are not mentioned; perhaps the employees’ families were present, the dependents. She’s a lady with people around her, and after her choice, her employees also accept Paul’s preaching and become Christians. Starting from that place, Paul begins his preaching activity and makes a gesture of liberation to a slave girl who was exploited because she had a spirit that could predict the future. We could say that she had paranormal powers. The narrator specifies that she is dominated by a demonic spirit that gives her these paranormal powers. As a child slave, she was exploited by the masters; she could read hands, do the horoscope to predict the future, and the money earned went straight to the masters’ coffers. When this girl sees Paul and the others pass by, she identifies them as preachers of the true God. For a few days, Paul lets her speak, then Paul intervenes and releases her.

It is interesting to reflect on this because the girl is making positive publicity for Paul. She is indicating to the people that this man and his companions are preachers of the true God. Still, Paul does not accept to be complicit with the action of those masters who exploit that diabolic power and release her from those paranormal powers. The girl is free from the devil’s grip, but without the qualities that gave profit to the masters, who, seeing a profit fade away, denounce Paul as a dangerous character that disturbs the social balance.

Romans mainly inhabited the city; the masters had to be Romans, and the imperial authority arrested Paul and Silas without too much discussion. The soldiers mistreat them, beat them, and throw them into the deepest cell of the prison. That night, while they are sore from the beating and mistreatment they suffered, Paul and Silas are at prayer; they recite psalms, sing hymns that they know by heart. Let’s imagine the scene of a dark subway prison where you hear the delicate voice of two men who are praying, and suddenly there is an earthquake. The prison shakes, the doors open wide, the soldiers are terrified, the prison guard, in charge of the prison, is afraid that in that tumult the prisoners have escaped, he lights a torch and enters to see, and Paul stops him from hurting himself, guaranteeing: “We are all here.” That man is surprised and amazed at Paul’s serenity and security. He kneels before him and asks him what he has to do to save himself, and Paul takes advantage of that opportunity which appeared decidedly negative and made it a good occasion for the evangelical announcement; he evangelizes the correctional officer, a Roman who takes the prisoners home, washes their wounds, cures them where there is a need for a healing intervention; feeds them, gets baptized, and becomes a Christian.

It is an inversion of destiny; it is an Easter night, a night of liberation, a light is lit from the darkness. From the darkness, from the negative and violent attitude of the soldiers, one passes to the luminosity of the benevolent encounter. He who had wounded becomes a healer; he who had the apostles imprisoned becomes a liberator, but in reality, he has been liberated. We also observe the other paradox: Paul, who freed the girl from this paranormal power, is imprisoned because he who liberates gives annoyance to the corrupt structure of the world.

The imprisoned liberator is still a liberator and frees the jailer who, from violence, becomes a benefactor; he kneels to wash the apostles’ feet. The washing of the feet scene comes to mind; the jailer at Philippi knows nothing yet of Jesus; it is only because of the esteem, the wonder that Paul has provoked in him, and he becomes an imitator of Christ. Once baptized, he becomes a participant in the life of Christ. He discovers that Paul is a Roman citizen, and they couldn’t have treated him that way. The city leaders, finding out about this, wanted to set him free without saying anything, but Paul stands firm, says: ‘You have walked us in public, and now you’re secretly letting us go. NO. Let the authorities come and free us by publicly acknowledging that they have been wrong in their behavior.’ Paul is very humble, he gets beaten up, but he knows the law and, pedagogically, wants the procedure to be recognized as wrong.

Philippi was a beautiful opportunity for evangelization. In that city, a beautiful Christian community was born that remained in contact with Paul for a long time; years later, the apostle will write to the Philippians, that is, to the Christians who lived in the city of Philippi. And at least we know this lady Lydia and the jailer because he is baptized with those in his house. There are already two houses, two ‘domus ecclesiae,’ two places of the Church, two Christian communities that later probably multiplied. The letter to the Philippians is addressed to that community. Paul leaves the city of Philippi and proceeds along the main road, the great Roman connecting artery, called Egnatia, arrives in the city of Thessalonica, capital of Macedonia and also in Thessalonica begins the evangelizing activity, starts from the synagogue; finds difficulties; also, in this case, must face opposition and persecution.

He is not arrested because he was not found at home, but they arrested the one who gave him lodging; his name is Jason, and he is released on bail; as if to say, if Jason gives them Paul, he can get back the money he had to pay as bail. Jason would rather lose that money and make Paul escape. Paul quickly leaves Thessalonica and will not return there anymore because there was a reward on him, and therefore, it was dangerous to return to Thessalonica. He moves to Berea and then decides to go down south.

Luke stops at Philippi. How do we know? The narrative returns to the third person; instead of saying ‘we went,’ he says ‘they went.’ It means that the journey continued with Paul, Silas, and Timothy. Luke stops in Philippi; Timothy and Silas stop in Thessalonica and Berea. And Paul continues alone; he arrives in Athens alone. He has left his collaborators to follow these young communities that had just been born in the cities of Macedonia. The Gospel reached Europe.