Blogs

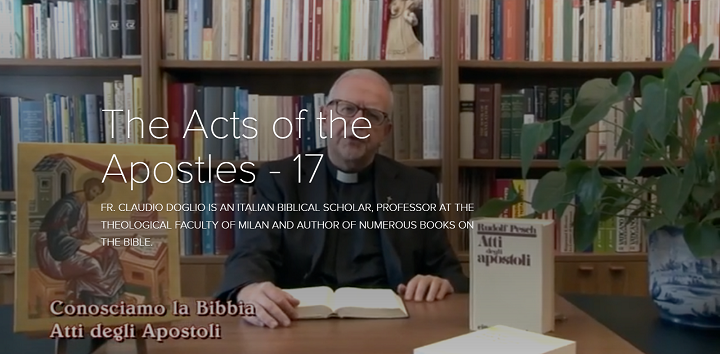

17. Paul’s Arrest in Jerusalem

Acts of the Apostles

In the spring of 58, the apostle Paul left Philippi in Macedonia, where he had celebrated the feast of the Unleavened Bread, that is, the Passover, and left to go to Jerusalem. He arrived there for the feast of Pentecost, so the journey took about 50 days, and it was an opportunity for Paul to see many communities he had founded and led in previous years.

Chapter 21 of the Acts of the Apostles tells us about the apostle’s arrival in Jerusalem with a rather complex situation. Paul knew that he would encounter a painful situation and foresaw that he would be arrested because a negative opinion had already spread about him in the Jewish milieu; he was accused of going against the law, a ruin of the Jewish tradition. Paul began to preach in the synagogues starting from the biblical texts, but announcing the newness of Jesus Christ and, therefore, bringing a great breath of fresh air into Jewish tradition. He announced that Christ is the bearer of the divine grace, which completes and fulfills the law.

Just before, in the winter between 57 and 58, Paul had written the letter to the Romans to present his doctrine; he calls it ‘his gospel,’ to that community that he had not founded and where he hoped to go soon. The Christian community in Rome, formed mainly by Jews, was very important because it was in the empire’s capital. To make those people aware of the correct teaching seemed to Paul to be a proper way to fight the bad news that circulated about him. He maintains that we are no longer under the law but under grace; this does not mean that the law has been abolished; it means that grace makes us capable of doing what the law says without giving us the strength to carry it out.

Therefore, it is a preaching of great openness, hope, and novelty; it is preaching that announces the possibility of living well, a possibility that God gives through Jesus Christ. The central event of Christ is his Easter of death and resurrection. Paul becomes an imitator of Christ, and like Jesus, he goes to Jerusalem to fulfill God’s plan. He feels in himself a prediction of anguish, of pain, of suffering. He is an imitator of Christ and bravely continues to follow in his footsteps.

In Jerusalem, Paul meets the Jewish Christian community, for which James was responsible. We know him as James the Less. In tradition, he is called the Lord’s brother. He was a relative of Jesus, most likely his cousin, who was in charge of the Christian community living in Jerusalem because he was related to Jesus himself. The Christian tradition does not consider Peter the first bishop of Jerusalem but James, and James, the head of the Jewish Christians of the mother church in Jerusalem. Today, we could say the leader of the conservatives, while Paul is an important exponent of the progressives.

At that moment, on the feast of Pentecost in 58, James and Paul meet and reunite fraternally. However, James points out to Paul that there is much bad news about him, that is, he is accused of breaking the law, of profaning the sacred things, and the moment Paul is in Jerusalem, the risk will be that of being accused of defiling the temple, that is, of bringing non-Jews into the sacred temple enclosure. Paul’s activity was above all to announce the gospel to non-Jews and open the door of faith to all peoples and cultures, to all the people he met in his innumerable movements. Many of these are their companions.

The narrator of the Acts listed them by name, presenting them as coming from many different cities in Anatolia and Greece. Some of them are pagan; they come from the Greco-Roman world. They are not Jews, and on principle, Paul did not ask them to be circumcised because he taught that circumcision was not necessary, not necessarily indispensable to salvation. He made a serious effort in this regard to make it clear that for salvation, only Jesus Christ is necessary; faith in Christ is sufficient for salvation.

James is concerned that Paul’s presence be misunderstood and therefore asks Paul to make a gesture of humility, enter the temple with a penitent attitude, offer sacrifices of reconciliation, and pay the offerings for other brothers who had made promises. James asks Paul to show his respect to the Jewish world. Paul does not want to be a provocateur; he is not a profaner, does not dispute the law itself, so James asks him to give a sign that he is still behaving like a good Jew. James asks him to do things like a pious Israelite coming to Jerusalem who enters the temple to obtain purification of sins.

And Paul accepts. “So Paul took the men, and on the next day after purifying himself together with them entered the temple to give notice of the day when the purification would be completed, and the offering made for each of them.” It was the week of preparatory rites that were needed to reach the moment of the dissolution of the vow and obtain the declaration of purity. Hence, Paul went to the temple several times, dressed impeccably according to the Jewish style, along with many other people; therefore, in the immense confusion that reigned in the temple’s esplanade, he went unnoticed for several days.

“When the seven days were nearly completed, the Jews from the province of Asia noticed him in the temple, stirred up the whole crowd, and laid hands on him, shouting, ‘Fellow Israelites, help us. This is the man who is teaching everyone everywhere against the people and the law and this place, and what is more, he has even brought Greeks into the temple and defiled this sacred place.'” It was what he feared. Some of the Jews from the province of Asia that is, especially from Ephesus, who had known Paul in the three years of his stay in Ephesus, recognized him and shouted, accuse him with slander, were those common arguments circulating in the Jewish environment opposed to Paul.

He did nothing of what he was accused of. Still, it is enough to use such a delicate subject as the desecration of the temple to excite the spirits, and that mass of people certainly do not go for the subtle to investigate whether it is true or not; they accept the accusation and throw themselves at him. “For they had previously seen Trophimus the Ephesian in the city with him” one of Paul’s disciples, a Greek converted to Christianity without passing through Hebraism “and supposed that Paul had brought him into the temple” something absolutely forbidden, something that Paul had not done. Still, slander is a breeze that begins slightly but then comes thundering in, and the storm breaks.

The people rage against Paul, who risks a lynching. He was referred to the tribunal of the court since all of Jerusalem was in revolt. At that time, the governor of Judea was absent; he went to Jerusalem usually only for the festivities, when riots were expected. Usually, the garrison of Roman soldiers that resided in the temple, in the Antonia fortress, was directed by the court commander who resided in the Antonia fortress, the same fortress built by Herod the Great and dedicated to Mark Antony, where Pilate lived, where Jesus was brought for trial before Pilate.

We are in the year 58, while the condemnation of Jesus had taken place in the year 30. Twenty-eight years have passed. In the same environment between the temple and Antonia Fortress, Paul’s arrest occurs. The risk of lynching stops because the commander intervenes with the soldiers, quells the revolt, sees a man being beaten, makes his arrest, takes him to the prison located in the Antonia fortress. The Antonia’s fort was connected to the temple; a stairway gave access to the temple.

Of course, the Jews who frequented the temple did not set foot in the Antonia fortress, considered an unclean place. Remember that Jesus’ accusers did not enter the praetorium to avoid contamination because if they step into that Roman environment, it means getting dirty, contaminated, and not being able to celebrate the Passover. Instead, the Roman soldiers used that passage to enter the temple esplanade and control the situation, which very often degenerated into fights, as in this case.

Therefore, Paul is taken out of the popular lynching and carried on from that staircase to the Antonia Fortress. “May I say something to you?” He replied, “Do you speak Greek? So then you are not the Egyptian who started a revolt some time ago and led the four thousand assassins into the desert?” Of course not, Paul says. The commander is surprised that he knows Greek; in general, these people know only Hebrew or Aramaic and therefore must have been used to not understanding their interlocutors and is astonished that this character speaks fluent Greek. “Paul answered, ‘I am a Jew, of Tarsus in Cilicia, a citizen of no mean city; I request you to permit me to speak to the people.'” The commander thinks it is feasible. They are now safe, on the steps where observant Jews do not step; the Roman soldiers are around, making a wing around the prisoner free to speak to the crowd.

The people have gathered, there is a great crowd at the foot of that staircase, and Paul takes advantage of the opportunity of his position; he starts a speech and speaks in Hebrew. With the commander, he has spoken in Greek, with the crowd of Jews speaking in Hebrew. Chapter 22 narrates this apologetic discourse; that is, it is the umpteenth time in which Luke, the narrator of the Acts, puts in Paul’s mouth a speech where he tells his own experience.

Paul begins to tell of his situation as an observant Jew, born in Tarsus of Cilicia but raised in this city, trained at the Gamaliel school in the strictest rules of parental law. People who hear him speak in Hebrew make silence and listen to him. As a good rhetorician, Paul begins with a ‘captatio benevolentiae,’ that is, remembering all his former position as an observant Jew who followed the laws of Israel and was a student of an important personage like Rabbi Gamaliel. But then Paul relates the encounter with Christ, an important episode on the road to Damascus, that life-changing experience of the Risen Christ.

Meeting the Risen Lord was for Paul the fulfillment of his religious experience. He did not convert but matured and became a real Jew; he realized the project that the law had given him and that he had taken in since he was a child; he realized that Jesus brought him to fulfillment. He narrates the difficulties of the first moments and says: “After I had returned to Jerusalem and while I was praying in the temple, I fell into a trance and saw the Lord saying to me, ‘Hurry, leave Jerusalem at once, because they will not accept your testimony about me.'” The Lord warned me, and they did not accept my word, but the Lord said to me—Paul continues addressing to the multitude of Jews— “Go, I shall send you far away to the Gentiles.” He received a missionary assignment for all people. “They listened to him until he said this, but then they raised their voices and shouted, ‘Take such a one as this away from the earth.’”

It is the same environment where 28 years before, they had shouted to Pilate to kill Jesus; now, others cry out to this commander to have Paul killed. They were yelling and throwing off their cloaks and flinging dust into the air; the cohort commander ordered him to be brought into the compound and instructed that he be interrogated under the lash.

Paul allows himself to be whipped with the straps, but when they had stretched him out for the whips, Paul said to the centurion on duty, “Is it lawful for you to scourge a man who is a Roman citizen and has not been tried?” When the centurion heard this, he went to the cohort commander and reported it, saying, ‘What are you going to do? This man is a Roman citizen.’ Then the commander came and said to him, “Tell me, are you a Roman citizen?” “Yes.” The commander replied, “I acquired this citizenship for a large sum of money.” Paul said, “But I was born one.”

On the other hand, Paul is proud of having been born a Roman citizen; as an inhabitant of Tarsus, he had this privilege since, at that time, Mark Antony had granted the inhabitants of Tarsus to become Roman citizens automatically. Therefore, the apostle enjoys this civil privilege and uses it to block such unjustified punishment. The commander is afraid of this complicated situation and thinks he can solve the problem by sending this prisoner before the synedrion.

The man he arrested is polyhedral; he is a Roman citizen who speaks Greek fluently but is a law-abiding Jew who can speak Hebrew according to tradition. He is a man of great courage; the commander realizes that the crowd is angry with him for some strange reason, but which has nothing to do with Roman law, so he wants to get it off his chest, making the synedrion judge him, so he moves him to the synedrion room that was in the big construction of the temple in Jerusalem, and the accused, at this point, is questioned by the highest authorities of the Jewish world.

Paul begins immediately with a decision: “‘My brothers, I have conducted myself with a perfectly clear conscience before God to this day.’ The high priest Ananias ordered his attendants to strike his mouth. Then Paul said to him, ‘God will strike you; you whitewashed wall. Do you indeed sit in judgment upon me according to the law and yet in violation of the law order me to be struck?’ The attendants said, ‘Would you revile God’s high priest?’ Paul answered, ‘Brothers, I did not realize he was the high priest.’ For it is written, ‘You shall not curse a ruler of your people.'” Paul does not know this authority in person.

Ananias is a relative of that Annas who had questioned Jesus and Caiaphas, Annas’ son-in-law. The name is analogous; they are relatives. It is a closed priestly caste, and this group of Sadducees is questioning Paul even harshly, as they did Jesus; they slapped him just to keep him in submission. Paul, instead, reacts decisively and now uses cunning. Knowing that a good half of the members of the synedrion were Pharisees, like him, he tries to have the support of that side against the Sadducees and knowing that the Sadducees deny the resurrection while the Pharisees accept it, Paul introduces himself saying: “My brothers, I am a Pharisee, the son of Pharisees; I am on trial for hope in the resurrection of the dead.” “I am on trial for hope in the resurrection….” He does not specify that he believes in the resurrection of Jesus; he does believe in the resurrection, and because he preaches the resurrection of the dead comes accused… The group of Pharisees automatically supports him because it is a fundamental political idea, and the Pharisees argue that this man is not imputable and has full opportunity to present his views. They even raise the dose and say, “Suppose a spirit or an angel has spoken to him?”

Sadducees do not believe in angels. Now they add another argument of political theology that serves as a counterpoint. The Sadducees naturally shout the opposite, and forgetting Paul; the two groups collide with each other. Skilfully the apostle has divided the synedria by pitting one against the other. There was a great shouting; the dispute had been so heated that it seemed a scene of the Italian parliament in its worst days (!), where the different members jump to the center and start to hit each other. The commander was frightened, “The dispute was so serious that the commander, afraid that Paul would be torn to pieces by them, ordered his troops to go down and rescue him from their midst and take him into the compound.” There was nothing to be done. The trial play in the synedrion did not solve the problem.

“The following night, the Lord stood by him and said, ‘Take courage. For just as you have borne witness to my cause in Jerusalem, so you must also bear witness in Rome.'”