Blogs

10. Peter’s Release from Prison

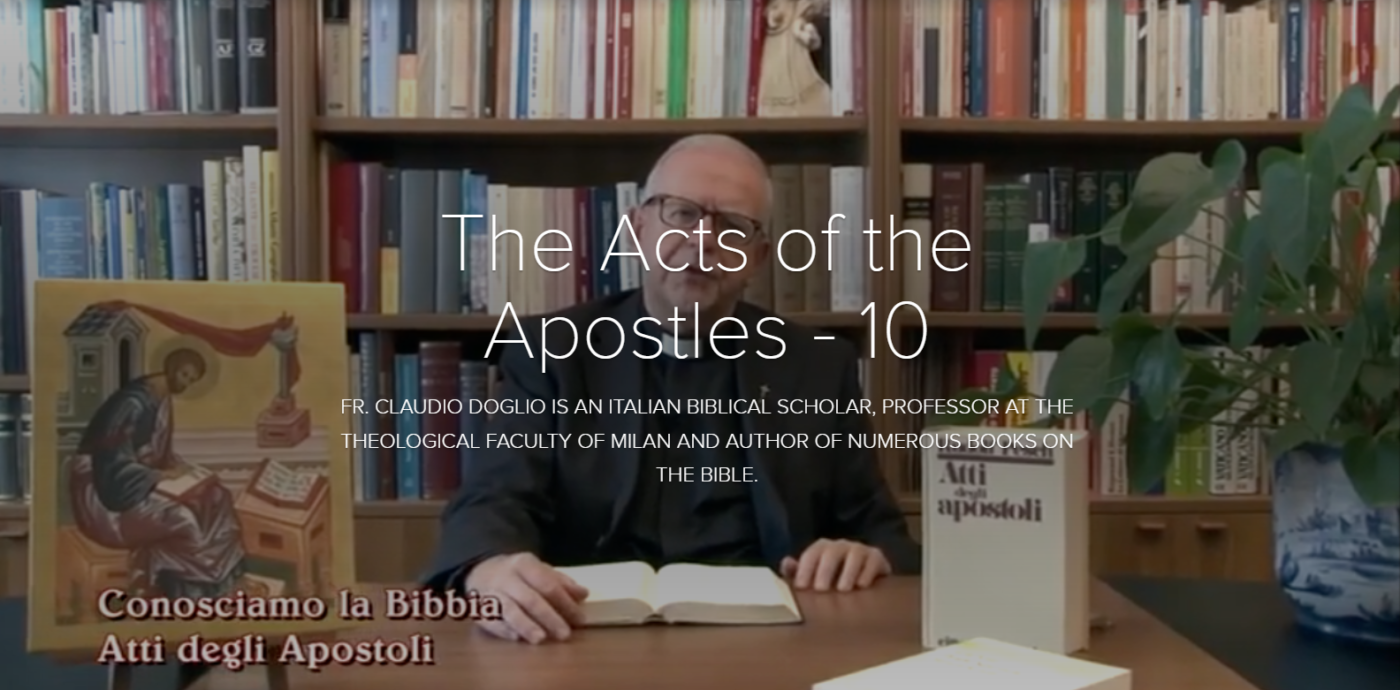

Acts of the Apostles

In Antioch, a Christian community was born of Greeks, that is, not Jewish people. This is an extraordinary fact. The Church of Jerusalem sent Barnabas to verify this strangeness, and Barnabas, as a virtuous man, recognized God’s grace; he went to seek Paul and took him to Antioch. The two remain in that great city and form many Christians. On this occasion, they learn of the famine afflicting the region of Judea. Therefore, in solidarity with the Mother Church of Jerusalem, the Church of Antioch sends financial aid to help the brothers and sisters of Jerusalem. Paul and Barnabas of Antioch go up to Jerusalem.

Thus ends chapter 11 of the Acts. Chapter 12 ends by saying: “After Barnabas and Saul completed their relief mission, they returned to Jerusalem, taking with them John, who is called Mark.” And it could be the closing of the story, but in the middle is chapter 12 there is a story about Peter. It is interesting to observe how the narrator used the separate story sources and tried to build them together, giving a unitary plot. The occasion of the journey of Barnabas and Saul to Jerusalem allows him to tell this new episode taking place in Jerusalem. And therefore, the two quotes of the trip to Jerusalem and back to Antioch serve as a frame of reference, one episode within another.

The story tells of when Peter was taken prisoner. The king who tries to oppress the Church with force is Herod. This is Herod Agrippa the First, is the grandson of that Herod Antipas who had ordered to kill John the Baptist and met Jesus during the passion. Herod Agrippa the First was a friend of Emperor Caligula, and in the ‘40s had obtained from his friend the emperor of the kingdom of Judea. They removed the governor and formed the autonomous kingdom of Judea. And this young offspring of the Herodian dynasty had the title of king; of course, it was very precarious and transitory, lasted just a few years, and Herod died tragically suddenly.

At the end of chapter 12, there are dramatic notes about the death of the persecutor, but the full content of the chapter is instead about the persecuted, which is Peter. “About that time, King Herod laid hands upon some members of the Church to harm them. He had James, the brother of John, killed by the sword.” The first of the twelve apostles to lose his life for Jesus is James. The famous ‘Santiago’ (James) venerated in Compostela in Spain. James, son of Zebedee, brother of John, one of the first apostles, one of Jesus’ closest friends. He was the one who in the Gospel had asked the first place, and he got it. The first place in the kingdom inaugurated by the Messiah Jesus is equivalent to the first to die. He was beheaded by order of Herod Agrippa the First.

We are, therefore, in the early years. Stephen was killed in the year 36, and the apostle James in the year 42. This seems to please the Jews; in other words, the different religious authorities in Israel appreciate this harsh attitude towards the Christians, those they called the ‘Nazarenes,’ the disciples of Jesus. And Herod, not because of personal convictions but out of political interest, seeing that this was pleasing to them, continues to do so; continues with this persecution and arrests Peter during the “feast of the Unleavened Bread.” That is the Easter celebration.

And here, Peter’s Easter is narrated. It is a story of death and resurrection. Precisely during the days of Easter, on the anniversary of the arrest of the passion and the death of Jesus, Peter is also arrested and imprisoned. Somehow it is his descent into hell, with an experience of liberation. The Acts of the Apostles relate numerous cases of open doors, of prodigious liberation of the apostles who are imprisoned by political and religious power and are released by divine intervention. If, in this case, the episode is narrated with many details precisely to underline this mystical participation on Christ’s Easter.

The apostle Peter stands in solidarity with Jesus in captivity and liberation. Herod has him in prison with the prospect of making him appear before the people after the Easter celebrations. He does not want to disturb the Easter solemnity; once the holidays are over, he plans to hold a public trial to make the event spectacular and condemn Peter to death, to obtain the title of paladin defender of Jewish traditions against these new heretical groups.

“Peter thus was being kept in prison, but prayer by the church was fervently being made to God on his behalf.” The Church’s prayer intervening on behalf of the apostle Peter becomes a weapon, a victorious weapon with which the prison doors are opened. “On the very night before Herod was to bring him to trial, Peter, secured by double chains, was sleeping between two soldiers, while outside the door guards kept watch on the prison.” He is kept under surveillance, controlled at sight, closed doors, with double chain, many soldiers were standing guard… “Suddenly the angel of the Lord stood by him and a light shone in the cell.”

The words are almost identical to the Christmas story; also, on the night in Bethlehem, an angel of the Lord appeared to the shepherds, and a great light shone. Now we are in a cell where there is a prisoner in chains. The angel of the Lord brings the good news; it is precisely the Gospel of God that frees him from the chains, “He tapped Peter on the side and awakened him, saying, ‘Get up quickly.’ The chains fell from his wrists. The angel said to him, ‘Put on your belt and your sandals.’ He did so. Then he said to him, ‘Put on your cloak and follow me.'” Peter came out behind him, not knowing if the angel was real because it seemed to him that it was a vision. It seemed to him a dream; the dark cell became shining; the chains opened by themselves, and the door opened. Peter has to get up, get dressed, and go out.

We are in a night of Easter, the liberation of the old Israel from the slavery of Egypt is remembered; now the apostle Peter is released from his cell, he stands up, gathers himself, and starts the way of the exodus. It’s a way out, and it is reality, what seems to be simply a dream. “They passed the first guard, then the second, and came to the iron gate leading out to the city, which opened for them by itself. They emerged and made their way down an alley, and suddenly the angel left him.” Repeatedly the verb ‘to get out’ is used: the chains have loosened themselves; the doors have opened themselves, and the apostle comes out of the cell, goes out of the hall, leaves the prison, and is in a deserted city in the middle of the night.

There is no one; he is left alone; he realizes that the person who freed him is the angel of the Lord. “Then Peter recovered his senses and said, ‘Now I know for certain that the Lord sent his angel and rescued me from the hand of Herod and from all that the Jewish people had been expecting.'” It is a prodigious intervention of liberation, an Easter intervention in which the apostle experiences the liberating power of the Gospel. He thinks for a while, tries to decide what to do, and then “when he realized this, he went to the house of Mary, the mother of John, who is called Mark, where there were many people gathered in prayer.” Mark is the evangelist; he is an important person in the first Christian community.

Here they give us another important piece of news, his mother’s name is Mary, and she is the house owner where the Church meets. It is a night when the community is awake and praying, and most likely it is Easter night; they are celebrating the Easter Vigil, and Peter arrives free, resurrected, while everyone thinks he is in jail. The house of Mark or his mother Mary is the Cenacle; it is the building where the apostolic community had celebrated the Last Supper and was present on Easter Day, then on Pentecost Day.

Now 12 or 15 years have passed, and the community continues to meet in that house. It has become the natural environment where the Jerusalem Christian group is located. “When he knocked on the gateway door, a maid named Rhoda came to answer it. She was so ecstatic when she recognized Peter’s voice that she ran in and announced that Peter was standing at the gate instead of opening the gate. They told her, ‘You are out of your mind.’ They told her that it couldn’t possibly be Peter. Peter is in jail. ‘But she insisted that it was so.’” They try to explain the phenomenon by saying that he is ‘Peter’s angel,’ almost a ghost or the divine alter ego.

It is a Jewish attempt to explain the presence of Peter, who cannot be in the flesh there. Peter is truly there, in the flesh, and continues to call, knocks and knocks harder and harder because they don’t open. Finally, “when they opened it, they saw him and were astounded. He motioned to them with his hand to be quiet because everyone was talking and wanted to know; he told them how the Lord had gotten him out of prison. And he added: “Report this to James and the brothers.” He is James the Lesser; the other James of the Twelve, also called James is ‘James the Major.’ This James was killed sometime before.

The Christian community of Jerusalem recognizes in James the Lesser, son of Alpheus, a relative of Jesus, their first bishop that is head of the Christian community of Jerusalem. The authority in Jerusalem is not Peter but James considered shepherd of that Jewish group. James and the brothers are not present in Mark’s house. That is probably one of the Christian groups that have become numerous by now; we have found the number 3000… 5000, and they do not fit in a house, so there must be more places.

Peter went to the closest house and said good-bye because he decided to leave Jerusalem, no longer a suitable place for him. He instructs this group to tell James and the other communities in Jerusalem that Peter has gone away. Indeed, from this moment on, Peter disappears from the horizon of the Acts; he will reappear in chapter 15 for a speech at the Jerusalem Council, but about his mission to the world, Luke does not speak.

With these narrations, Luke is practically finishing the stories about the apostle Peter, but we know that the book of Acts is not the biography of either Peter or Paul; it is not the history of the Church but a history of stories, of exemplary narratives, which Luke skillfully wove to communicate important ecclesial messages.

“At daybreak, there was no small commotion among the soldiers over what had become of Peter. Herod, after instituting a search but not finding him, ordered the guards tried and executed.” The powerful bully who wanted to crush the humble was, in fact, disappointed. He had prepared a spectacular day, but the show ended in a soap bubble; the prisoner was gone. With all the guards placed to control the man, how could they have let him escape? And in Jerusalem, there was no trace of Peter.

The apostle had wisely walked away because he realized that he would be sought out with particular fury. Luke ends this painting by highlighting the tragic end of King Herod Agrippa the First and relates with gloomy tones a fact also mentioned by other sources of a sudden and public death. Herod lived in Caesarea-Maritima; he moved to Jerusalem for the holidays. And, precisely during the feast of Passover was preparing the trial against Peter. After that moment, which was one of frustration, he returned to Caesarea. “Herod had long been very angry with the people of Tyre and Sidon, who now came to him in a body. After winning over Blastus, the king’s chamberlain, they sued for peace because their country was supplied with food from the king’s territory.

On an appointed day, Herod, attired in royal robes, and seated on the podium, addressed them publicly. The assembled crowd cried out, ‘This is the voice of a god, not of a man.'” It is a political scene that has nothing to do with the history of the apostles. In the court of Caesarea, King Agrippa the First receives the ambassadors of Tyre and Sidon; he gives a solemn speech, and the flattering people praise him as a god and at that moment of maximum splendor, dressed in the royal mantle, the justice of God strikes him: “At once, the angel of the Lord struck him down because he did not ascribe the honor to God, and he was eaten by worms and breathed his last.” He broke down… in that moment of triumph, he had a stroke, an ictus, or a similar illness. He felt bad and fell to the ground, fought and died in public, in front of all the sycophants in the court, wrapped in the royal mantle. It may have been some intestinal problem… These worms enter almost like an apocalyptic motive; in fact, what is said in the Magnificat is dramatized: “He deposed the powerful from their thrones and raised the humble.”

Peter is released from prison; Herod is deposed from the throne. The angel of the Lord frees the humble from their prisons and brings down the powerful from their thrones. “But the word of God continued to spread and grow.” This is the usual verse, almost as a leitmotif that Luke repeats from time to time. It is a suture thread, from sewing to join one story to another. This scene, set in Jerusalem, ends with an appendix in Caesarea, where Herod Agrippa and Peter are the protagonists.

The following verse takes up the thread of the speech: Barnabas and Saul, who had come to Jerusalem to bring the financial aid, return to Antioch and take with them that John we found in the Cenacle house, nicknamed Mark. They both bring Mark with them and will become three new missionaries that from Antioch will go around the world.