Blogs

15. Paul’s Third Trip

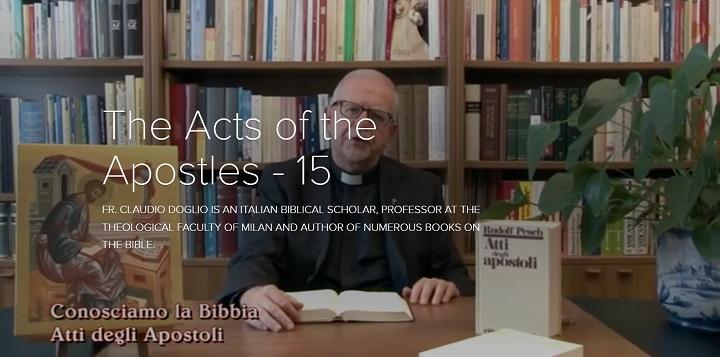

Acts of the Apostles

Antioch was the mother city of Paul’s apostolate. There he had begun at the invitation of Barnabas and Paul always returns to Antioch after his travels. At the end of the second great missionary journey, which led the preaching of the Gospel in Europe, Paul leaves Corinth and, after a brief stop in Ephesus, returns to Antioch, where he spends about two years in peace and quiet. It is hard to imagine Paul resting there, but at least he doesn’t move in the extensive operation of church planting, but he doesn’t stay still for long, and the third great apostolic journey begins. At the beginning of the second journey, crossing Anatolia, Paul intended to reach Ephesus, the capital of the province of Asia. Still, incidents on the way that Luke, the narrator of the Acts, does not precise, took him elsewhere. This time the apostle arrives there and stays for three years, approximately from the years 54 to 57.

The mission in Ephesus produced a great result. The city of Ephesus was a significant city since classical antiquity and the environment in which the philosophy of the first philosophers was born in the tradition of Aristotle, which we still study today in our books on the history of philosophy. It takes its momentum from the Ephesian environment; it is an environment not only of culture but also of religion; in the city of Ephesus, the temple to the goddess Artemis was erected, one of the seven masterpieces considered wonders of the ancient world, with a statue representing the goddess Artemis and believed that had fallen from the sky. Therefore, a sacred object of particular devotion was admired and revered by all the Greeks of the Mediterranean. This means that the Artemisian of Ephesus, a Greek bronze statue, was a place of pilgrimage from all the devotees of the ancient world. This produced a vast trade in religious tourism and the sale of sacred objects.

The atmosphere of the temple of Artemis (the Roman equivalent of Diana) had also become a place of worship and research, a middle way between philosophy and theology; we could talk about theosophy or, more simply, about magic. In the Hellenistic world, the goddess Artemis, sister of Apollo, the hunter, the virgin of the woods, had become the image of Nature, in Greek, the ‘φύση’ ‘füsis.’ It represented all the forces of nature, and the study of these natural forces seeking to control them, dominate, use them for their benefit is the path followed by magic. To be able to use forces in nature is the ancestor of science, but on a superstitious level, the forces of nature serve magical purposes.

Ephesus was an environment of significant magical research with thinkers seeking esoteric paths of power. In this Ephesian environment, an attitude that today would be called ‘syncretism’ was dominant, that is, the ability to put together all the details, all the various religious elements that merge in a single ‘soup’ with many different ingredients. This syncretic attitude led the Ephesians to be welcoming people. Precisely because they had a great interest in having religious tourists, the welcome attention was developed because those who come from outside bring money. This acceptance of the various religious principles was merged in that unique cult of Nature (as in capital letter), with a single interest inside all the details. Paul understands this danger in a second moment; at first, he was surprised by the Ephesian reception because his preaching was readily accepted, and thinkers from very different positions, from philosophers of nature to magicians and scholars of spells and sorceries, were willing to accept the preaching of Jesus.

Later, Paul realized that this acceptance was modest, quite conditioned. Jesus was presented as a force and therefore was accepted, along with many other influences. If Jesus can do good, we take him and use him to do good, to take advantage for ourselves, placing Jesus also amid all the other forces of nature that we can consider, worship and use. Chapter 19 of the Acts of the Apostles recounts the beginnings of this evangelical preaching in Ephesus, where the apostle Paul has great success with exceptional popularity.

A nice episode is narrated in which some Jewish exorcists are presented, inserted in that Hellenistic environment, practiced their exorcism rites to free people who had such problems. Upon hearing Paul’s preaching, these Jewish exorcists take the name of Jesus and use it. If they get results with that name, they use it and adopt it.

“Some itinerant Jewish exorcists tried to invoke the name of the Lord Jesus over those with evil spirits, saying, ‘I adjure you by the Jesus whom Paul preaches.’ When the seven sons of Sceva, the evil spirit said to them in reply, ‘Jesus I recognize, Paul I know, but who are you?’ The person with the evil spirit then sprang at them and subdued them all. He so overpowered them that they fled naked and wounded from that house.” That demon man beat all seven of them; he stripped them naked and threw them out of the house.

The scene is interesting, ridiculous for us, but not for them. They are people who used the name of Jesus; they have abused the name. They are Jews present in Ephesus because they were taught many tricks, and as Jews practice exorcism and use the name of Jesus as one of many tricks to obtain some therapeutic result. The evil spirit recognizes Jesus and recognizes Paul, but it does not know them. This means that there is no effective relationship of these people with the name of Jesus, but a superficial and self-serving adherence that ends badly; they were treated with holy anger.

Paul’s preaching produces social effects to the extent that “when this became known to all the Jews and Greeks who lived in Ephesus, fear fell upon them all. Many of those who had become believers came forward and openly acknowledged their former practices. Moreover, a large number of those who had practiced magic collected their books and burned them in public.” It is the beginning of an operation that, in other times, was negative, but in this case, it was people who rejected the previous culture; they burned their books on magic, believing they were wrong. This is a sign of change. It was not others’ books that were burned but their own, which were now considered harmful.

There is a change of mentality that marks the culture of Ephesus. And another effect that had to be considered was the decrease in the sale of religious objects; the statuette of the Artemis of Ephesus, manufactured in all sizes, in all metals and various materials were sold as one of the main objects of attraction, both commercial and religious. Paul’s preaching, which keeps away from idols, reduces the sales of Artemis figurines. The silversmiths, the confederation of Ephesus, the union that produced silver objects, feel harmed by this preacher who behaves in a politically incorrect manner. The head of the silversmiths’ union creates a riot in the city, provokes his colleagues who crowd the theater and shout against this foreigner from the East, a Jew, not from this community, who comes to Ephesus to ruin the market and therefore is undoubtedly a criminal … and moving the interest of the people, preaching to the people’s stomach, moving the lowest instincts, especially playing the economic question, they manage to have a large audience. This crowd perjured itself against Paul.

Luke, the narrator of the Acts, reproduces the speech of the silversmith with many details and the address of the chief of the people who intervenes to calm the waters, to prevent a riot. Whether it is a political issue or, worse, a criminal matter, we will judge against this person and punish him accordingly. But for the time being, he dissolves the assembly to avoid a revolt of the people. Paul is arrested and ends up in jail. We know from his writings that he even receives the death penalty in this environment, seriously risking being eliminated.

In these three years of his stay in Ephesus, Paul wrote the letters to the Corinthians, the letter to the Galatians, and the Philippians. He writes the note to Philemon to release that slave he met in prison, precisely during this detention. We don’t know what happened next, but the intervention of some person with authority has obtained the change of punishment; the death penalty is exchanged for exile, and Paul is forcibly removed from the city. Perhaps it was Aquila, the important Jewish textile entrepreneur who had already welcomed Paul in Corinth and who had now opened a new business in Ephesus and probably knowing the Roman authorities were able to change the sentence imposed on the Apostle Paul, but this is only a hypothesis because Acts does not speak of it. Paul himself, in the letters, says that he received the death penalty, but then God in his mercy set him free.

When, at the end of the letter to the Romans, he greets Aquila and Priscilla, he says that they risked their heads to save the apostle’s life in Ephesus; it could be a clue to reconstructing the things I have mentioned. Paul must leave Ephesus, moves to Macedonia, to Philippi, returns to where he had been a few years before, and then descends to Corinth and spend the winter there between the years 57 and 58. Paul writes the letter to the Romans; a few quiet months, the weather on the Isthmus of Corinth is pleasant and in Gaius house Paul dictates to a scribe named Terse, his masterpiece, the letter to the Romans, a theological treatise about salvation based on faith. Christ makes us righteous through faith.

In spring, he resumes his trip to Macedonia, celebrates Easter in Philippi, and after the days of the unleavened bread, together with Luke, he continues his journey. How do I know that Luke was there too? Because again, at this point, the narrative returns to the first person plural. Starting from Philippi, the narrator says: “We sailed from Philippi after the Feast of Unleavened Bread….” And if in the previous section Paul had stopped at Philippi, it means that Luke arrived in Philippi around the year 50 and remained there at least until the year 58, when he left together with the Apostle Paul. From Easter to Pentecost during the year 58, Paul moves to Jerusalem.

It is a long journey from Northern Greece to Jerusalem; they change ships several times, make small coastal navigation, touch many cities until at Pentecost they arrive in the capital, in Jerusalem. The first stage of this journey to Jerusalem is Troas, where Luke tells a particular episode, one of the rare occasions when the celebration of a Mass is narrated. Paul participates in the meeting on a Saturday afternoon, together with the Christian community living in Troas; they meet in a house; they are on the third floor, many people are listening to the apostle, and the Eucharistic celebration is led by the apostle who gives a long speech; it is formative evangelical preaching. This long preaching makes a boy sitting at the window fall asleep and fall from the third floor. His name is Eutico, a Greek name, which in English translates as ‘lucky’; he is a lucky young man who falls from the window and dies during a mass. Imagine the panic of the people present; they run downstairs, and Paul picks up this boy, telling people to stay calm because the boy lives. He breaks the bread, that is, he performs the central Eucharistic rite, then he keeps on talking to people until the morning, and when he finishes, the lucky boy is fine, he gets up, and he’s alive. It is a Mass that raises the dead.

It is an interesting story with which Luke presents the Apostle Paul, announcer of a life-giving gospel that communicates a life force. Participation in the Eucharist gives new energy to people who participate with heart, interest, and passion. Leaving Troade, “We went ahead to the ship and set sail for Assos,” and there they embarked. Luke is careful to list the group of disciples who accompany Paul: “Sopater from Beroea, Aristarchus and Secundus from Thessalonica, Gaius from Derbe, Timothy, and Tychicus and Trophimus from Asia” that is to say, natives of Ephesus. To them, we must add Luke, who was from Antioch.

We have a large group of disciples who accompany him, assist him, and collaborate with him, people of whom we know nothing, only the name and the city of origin. It means that from every city where Paul founded a community, someone joined the apostle and followed him to share his missionary work. Luke carefully narrates the journey with the main stages. Being navigation along the coast, they go from island to island, first to the north of the island of Lesbos, then the Chios stage, then the stage in Samos, in front of Ephesus where Paul was for three years, where he met many people. So as not to waste too much time, they stop at Miletus, the port immediately south of Ephesus, and there he summons the priests of the city of Ephesus to whom he gives an important pastoral speech.