Blogs

19. Porcius Festus and Agrippa II

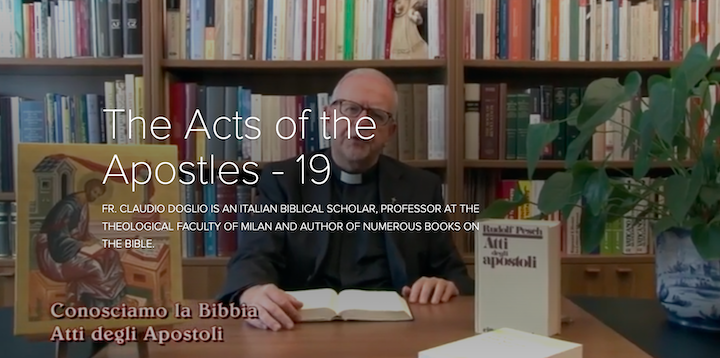

The Acts of the Apostles

In the spring of the year 60, in Caesarea Maritima, the governor of Judea was changed. Antonius Felix left the place to Porcius Festus. The new attorney general found that among the many cases to be solved there was also the question of a prisoner named Paul. For two years the apostle was held in Caesarea, in the Roman praetorium, awaiting trial; there were no serious reasons to accuse him, but the Governor Antonius Felix, on one hand, he wanted to please the Jews by keeping him in prison and on the other he expected the prisoner to pay a bribe to get free. Nothing having happened, Antonius Felix left the matter to Pontius Festus to resolve. “Festus went up from Caesarea to Jerusalem where the chief priests and Jewish leaders presented him their formal charges against Paul.”

The intention was always the same, as we have seen in the past, to violently eliminate Paul with an ambush during a transfer. “Festus replied that Paul was being held in custody in Caesarea and that he himself would be returning there shortly. He said, “Let your authorities come down with me, and if this man has done something improper, let them accuse him. After spending no more than eight or ten days with them, he went down to Caesarea.”

He is followed by some Jews who go precisely to accuse Paul and the judgment is renewed. Paul in his defense says that he is not at fault either against the law of the Jews, or against the temple, or against Caesar. The accusers cannot prove any accusation and Paul refutes them all. “Then Festus said, ‘Are you willing to go up to Jerusalem and there stand trial before me on these charges?’” He says: if you prefer to be judged by them it is possible.

Certainly, Festus wanted to get rid of the problem because he didn’t know which way to turn and offers Paul again the possibility of going to the synedrium. Paul rejects this possibility because he realizes that there is no openness to truth; no attitudes available for serious judgment and therefore plays its extreme card. “Paul answered, ‘I am standing before the tribunal of Caesar; this is where I should be tried. I have committed no crime against the Jews. If I have committed a crime or done anything deserving death, I do not seek to escape the death penalty; but if there is no substance to the charges they are bringing against me, then no one has the right to hand me over to them. I appeal to Caesar.’ Then Festus, after conferring with his council, replied, ‘You have appealed to Caesar. To Caesar you will go.’”

These are two very important formulas. Paul, as a Roman citizen, has the right to be judged by the imperial court in the capital, in Rome. It is a court of appeal; it is the last degree of trial as the various local courts have not had the courage to take a stand, Paul asks to be judged by Caesar, directly in Rome. Festus consults and of course its experts tell him that Paul is entitled to it and that it can be done; then the governor issues the sentence: “To Caesar you will go.” Since you have appealed to the authority of the emperor, you will be transferred to the capital of the empire and there you will face judgment. At least one decision has been made; Paul has been freed from the problem of Jewish judgment in the synedrion.

The move to Rome requires the right occasion and therefore the forced stay in Caesarea continues for some time. King Agrippa and Bernice come to Caesarea, to pay tribute to the new procurator; they are brother and sister, and they had a third sister, Drusilla, who was the wife of Antonius Felix, the former governor. Now they are going to visit the new governor because Agrippa, Herod Agrippa the Second, was king of Chalcidice, a small kingdom in the north of Transjordan (Lebanon), and therefore very close to the area of Caesarea Maritima. It is a state visit, is a courtesy visit; among the various things they discussed is also the case of the prisoner Paul. Festo tells him how things went, asking for advice since Agrippa and Bernice are Jewish and understand a little more of those religious themes that move the people.

Festus ends the presentation by saying that the prisoner appealed to Caesar. “‘I ordered him held until I could send him to Caesar.’ Agrippa said to Festus, ‘I too should like to hear this man.’ He replied, ‘Tomorrow you will hear him.’ The next day Agrippa and Bernice came with great ceremony and entered the audience hall in the company of cohort commanders and the prominent men of the city. Festo had Paul brought in.”

It is a solemn audience, all the authorities of the Galilee are present, and sit with a sumptuous attitude: King Agrippa, Princess Berenice, the Roman authorities and the prisoner Paul appears among them. Festus presents King Agrippa and all the honorable citizens present the case of this man. For his part, he admits that he does not know what to write to the emperor. ‘That is why I have presented it to you and especially to you, King Agrippa, so that after this interrogation I can write a report. “For it seems senseless to me to send up a prisoner without indicating the charges against him.” “Then Agrippa said to Paul, ‘You may now speak on your own behalf.’”

And Paul has an umpteenth apology. Paul defends himself making a self-defense speech. And once again, in chapter 26 of Acts, Luke presents a synthesis of Paul’s autobiography. It is an important and very extensive account; it takes up again the situation of the apostle’s life from the beginning, explaining to King Agrippa, who was well acquainted with the Jewish situation, that when Paul was young he belonged to the ‘airesis’ of the Pharisees, the most rigid sect of the Pharisaic group.

‘I served God night and day with perseverance, I was a fierce protestant of the preaching that was done in the name of Jesus the Nazarene. “Many times, in synagogue after synagogue, I punished them in an attempt to force them to blaspheme; I was so enraged against them that I pursued them even to foreign cities.” And once again, for the third time, we find the story of the Damascus road in which Paul, in the first person, tells that decisive event in his history. “I said, ‘Who are you, sir?’ And the Lord replied, ‘I am Jesus whom you are persecuting. 16 Get up now, and stand on your feet. I have appeared to you for this purpose, to appoint you as a servant and witness of what you have seen of me and what you will be shown.”

Paul has the knowledge that he has been made a minister and a witness. He had an official commission from the risen Christ. He has been called to be an apostle, a personal witness, he has experienced the risen Christ and therefore, becomes a credible witness to the things he himself has seen. He continues to report on the word the Lord said to him: “I shall deliver you from this people and from the Gentiles to whom I send you, to open their eyes that they may turn from darkness to light and from the power of Satan to God, so that they may obtain forgiveness of sins and an inheritance among those who have been consecrated by faith in me.”

Paul does not specify many other theological things to Agrippa, he simply explains that his position is that of a religious man who has matured the knowledge of Judaism, believes in the coming of the Messiah, has recognized that Jesus of Nazareth is the dead and risen Messiah and has spent his life making Him known to others. “And so, King Agrippa, I was not disobedient to the heavenly vision. On the contrary, first to those in Damascus and in Jerusalem and throughout the whole country of Judea, and then to the Gentiles, I preached the need to repent and turn to God, and to do works giving evidence of repentance. That is why the Jews seized me when I was in the temple and tried to kill me. But I have enjoyed God’s help to this very day, and so I stand here testifying to small and great alike, saying nothing different from what the prophets and Moses foretold, that the Messiah must suffer and that, as the first to rise from the dead, he would proclaim light both to our people and to the Gentiles.”

The end is solemn. It is a wonderful synthesis in which Paul shows how the Christian faith fits perfectly in Jewish tradition. ‘I have the faith of the prophets and of Moses, I believe that what has been announced has happened, the Christ is the first among the risen ones, thanks to him light comes to the people of Israel and to all other peoples.’ As Paul spoke in this way in his defense, Festus can no longer keep quiet and exclaims: “You are mad, Paul; much learning is driving you mad.”

He who speaks is a Roman, he is a man of law, he is a governor, a practical, very material person. All these discourses according to him are madness. This man has studied too much; it is an exaggerated knowledge and that is why studies have made him a maniac. “But Paul replied, ‘I am not mad, most excellent Festus; I am speaking words of truth and reason. The king knows about these matters and to him I speak boldly, for I cannot believe that any of this has escaped his notice; this was not done in a corner. King Agrippa, do you believe the prophets?’”

He addresses him directly at point-blank range, asks him a very personal question… “I know you believe.” Then Agrippa said to Paul, “You will soon persuade me to play the Christian.” Paul replied, “I would pray to God that sooner or later not only you but all who listen to me today might become as I am…!”. Then he realizes that his hands are chained and apologizes: “I would like them to become like me except for these chains.” ‘I certainly wouldn’t want them to become a prisoner, in a distressing situation like the one I am living now; I would like you to become like me, disciples of Christ.’

Agrippa listened to him carefully and it is not clear whether he does it out of mockery or genuine emotion: He admits, “You will soon persuade me to play the Christian.” You are convincing me. The speech is taking a turn that risks becoming serious and so they interrupt. “Then the king rose, and with him the governor and Bernice and the others who sat with them. And after they had withdrawn they said to one another, “This man is doing nothing at all that deserves death or imprisonment.” And Agrippa said to Festus, “This man could have been set free if he had not appealed to Caesar.”

Now another Jewish authority, Herod Agrippa the Second, suggests to Festo that he could be released. He is a man who deserves neither judgment nor condemnation. They probably pity him, don’t believe him, pity him in some way, believe that he is a religiously fanatical man with his high idealistic expectations, but he is not a criminal and is not a dangerous character.

He could be released, but there is that important resource, the prisoner is a Roman citizen, appealed to the emperor, and has the right to go to the imperial court and therefore now Festus no longer has the power to issue a sentence and decides that as soon as possible the prisoner will be transferred to Rome. The last two chapters of Acts, 27 and 28, narrate the long journey by sea that Paul must make in the transfer from Caesarea to Rome. “When it was decided that we should sail to Italy….”

Let us immediately note that chapter 27 begins with the first person plural. Until now the story was in the third person plural. In 27.1 the text speaks of ‘we.’ “When it was decided that we should sail to Italy, they handed Paul and some other prisoners over to a centurion named Julius of the Cohort Augusta.We went on board a ship from Adramyttium bound for ports in the province of Asia and set sail. Aristarchus, a Macedonian from Thessalonica, was with us.”

“He was with us….” It is Luke who is speaking, he is the author of the Acts. Paul is sent along with Luke and Aristarchus, a Christian native of Thessalonica, one of those who had followed Paul to Jerusalem in the year 58. Then Paul had been transferred to Caesarea, two years had passed waiting for the trial, and finally, in the fall of the year 60, the transfer begins.

And this last part of the Acts, written in the first person plural, takes as a source of reference that record book that Luke, Paul’s companion, probably wrote live, while the trips were being made. We have already found them in previous chapters; they are always stories of movements by sea where Luke refers to his presence in the group that accompanied Paul.

It is clear that the accuracy of the news depends on the notes he took while making these trips. The history of the transfer to Rome is very detailed, it presents names of people, of geographical places and with precise chronicle details narrates the evolution of this sea journey. Paul is entrusted to a centurion named Julius, of the Augustan cohort; this is the name of the marshal who must have him in custody.

Paul is bound in chains to a Roman soldier, evidently along with other prisoners and was boarded on a ship so that they could reach the capital. A transfer cannot be arranged for one man; they will have waited to have a certain number of prisoners to send to the Roman court and therefore, organize this navigation. The ship was headed for Adramyttium, and is destined for the ports of the province of Asia, the area of Ephesus. It is difficult to find a boat that goes directly to Rome; the lines of communication were drawn from these ships that made a regular service but always of small coasting, therefore, sailing from port to port, without venturing into the Mediterranean Sea. Therefore, the narrator carefully counts the different stages.

“On the following day we put in at Sidon.” From Caesarea they go north and stop in Sidon, therefore, a day of navigation and a night in the port. “And Julius was kind enough to allow Paul to visit his friends who took care of him.” On the way to Jerusalem they had stopped in Tyre, on the journey in which he is a prisoner they stop in Sidon. Also in Sidon there is a group of Christians and Julius treats Paul well and gives him a few hours of free time to meet the Christian community living in Sidon. Even as a prisoner Paul remains a missionary, the shepherd of the church.